Migraine Massage: Which Techniques Work, What Should You Expect, and When Might It Help?

Why Migraine Massage Matters and How This Guide Is Organized

Migraine isn’t just a bad headache; it’s a neurological condition that can bring throbbing pain, nausea, sensitivity to light and sound, and a stop‑everything urgency. For many people, muscle tension in the neck, shoulders, jaw, and scalp rides shotgun with migraine attacks, sometimes acting as a trigger and sometimes as an unwelcome side effect. Hands‑on care aims to soften that tension, support down‑regulation of the nervous system, and reduce the frequency or intensity of attacks for some individuals. While massage is not a cure, it is a non‑drug option that some people find useful alongside clinician‑guided treatments and lifestyle strategies.

This article focuses on practical, evidence‑aware guidance you can use right away. We’ll explore what techniques are commonly used for migraine, what a typical session includes, and step‑by‑step ideas for gentle self‑care. You’ll also find pointers on safety, red flags, and how to decide whether to try massage at home or work with a professional. The tone is realistic: gains tend to be incremental, and consistency matters more than any single session.

Here is how the guide is structured so you can jump to what you need most:

– Understanding where massage fits: muscle tension, the trigeminovascular system, stress, and sleep

– Techniques and evidence: trigger point work, myofascial release, craniosacral approaches, acupressure

– A 15‑minute self‑massage routine: step‑by‑step instructions and pressure guidelines

– Working with a professional: screening questions, what to expect, frequency, and aftercare

– Conclusion and action plan: how to track benefit, when to pause, and how to combine strategies

Why consider massage at all? Epidemiological research estimates that migraine affects roughly one in eight adults worldwide, with substantial effects on work, caregiving, and social life. Stress, posture, teeth clenching, and screen time can tighten neck and jaw muscles, which may prime the nervous system toward a lower threshold for pain. Massage aims to interrupt that cycle by easing myofascial stiffness, improving local circulation, and promoting a parasympathetic response (think: slower breathing, lower perceived stress). For some, that translates into fewer attack days or less intense recoveries; for others, it offers short‑term comfort when used thoughtfully during the postdrome or between attacks.

What Techniques Do: Evidence‑Aware Options and How They Work

Massage therapy is a wide umbrella, and not every method is ideal during a migraine episode. The goal is to reduce nociceptive input from tight tissues, calm the nervous system, and avoid overstimulation. Several approaches are frequently discussed in migraine care, each with its own rationale and touch profile. While research is growing, most studies are small; findings suggest potential benefits for attack frequency, intensity, and sleep quality when massage is used regularly over a few weeks.

Commonly used techniques and why they may help include:

– Trigger point therapy: Sustained, tolerable pressure on irritable spots in muscles like the upper trapezius, suboccipitals, masseter, and temporalis. Releasing these points can reduce referred pain into the head, temples, or behind the eyes.

– Myofascial release: Slow, gentle tensioning of fascia to reduce stiffness in the neck and shoulder girdle. The pacing is intentionally unhurried to avoid a flare‑up.

– Craniosacral‑style work: Light touch at the skull base, sacrum, and along the spine aimed at easing nervous system overactivity. Evidence is mixed, but some individuals report reduced headache days.

– Acupressure: Targeted pressure at points such as GB20 (base of the skull), Taiyang (temple region), and LI4 (between thumb and index finger). Some small trials suggest decreased headache intensity; avoid certain points during pregnancy unless cleared by a clinician.

– Gentle lymphatic or scalp massage: Support comfort, decrease a sense of fullness, and improve relaxation without heavy pressure.

What does the research say? Pilot randomized trials and small controlled studies have found that weekly sessions over 4–8 weeks can yield modest reductions in headache days and pain ratings, along with better sleep. Improvements often appear after several sessions, not immediately, and the magnitude of change varies widely. Mechanistically, benefits likely involve a combination of reduced muscle guarding, changes in local blood flow, and central modulation of pain (think: dialing down threat signals). Importantly, deep, aggressive pressure is rarely indicated for migraine and can backfire by provoking a delayed flare.

How to choose a technique? Start gentle, especially if you have allodynia (scalp tenderness) or are early in recovery from a severe attack. If light touch feels soothing, craniosacral‑style work or scalp massage may be appropriate; if jaw clenching is a factor, focused work on the masseter and temporalis may offer relief between attacks. A thoughtful therapist will combine approaches based on your symptoms, history, and response in real time. The unifying theme is calm, predictable touch with your informed consent at every step.

A 15‑Minute Self‑Massage You Can Try at Home

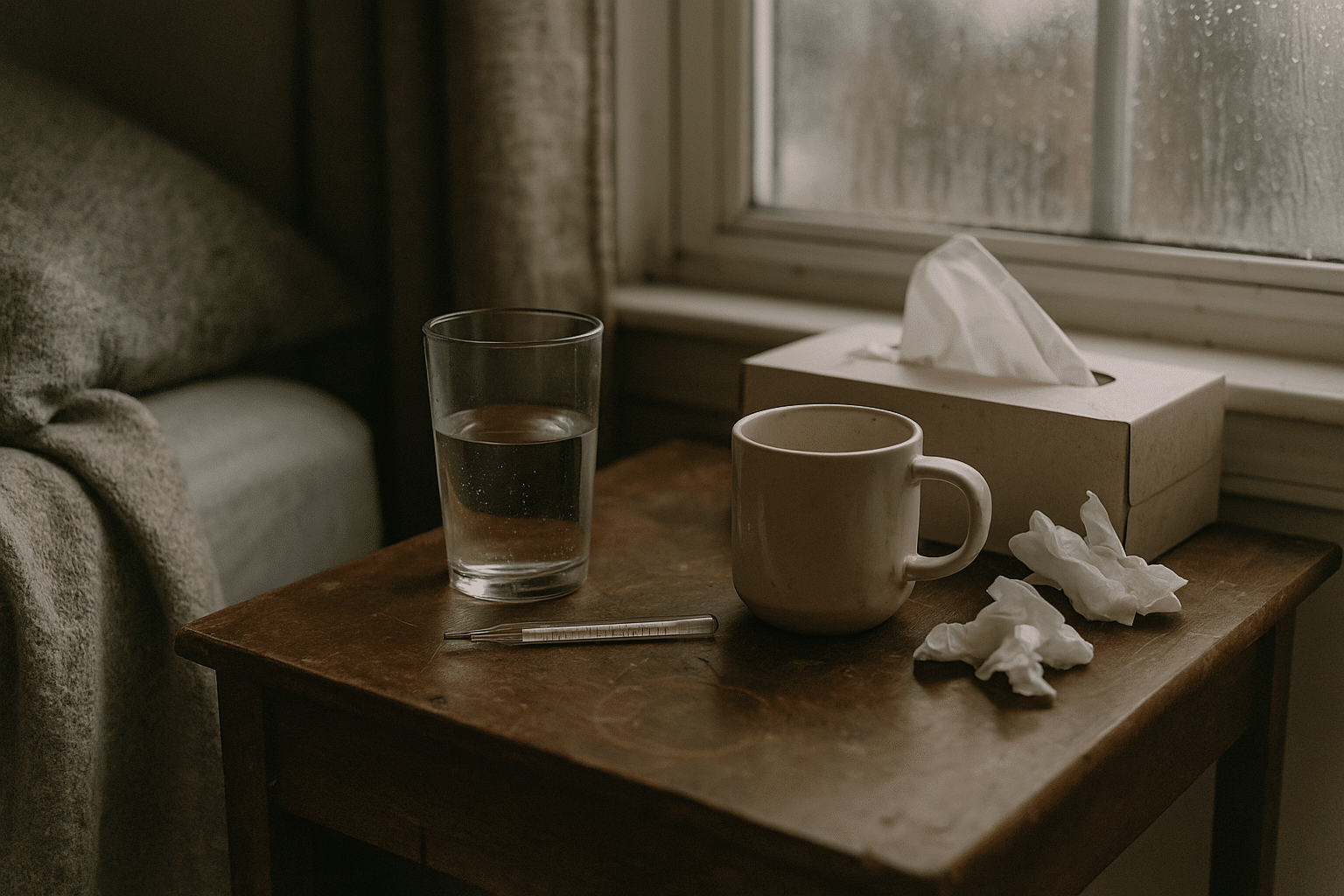

Self‑massage during a migraine should be gentle, brief, and driven by your comfort. The aim is to reduce muscle tension and foster a quieter nervous system without overwhelming your senses. Choose a low‑stimulus space: dim lights, reduced noise, and supportive seating. Keep water nearby, and use a small amount of unscented lotion or oil if it helps your fingers glide without tugging sensitive skin. If at any point your symptoms worsen, stop and rest.

Set the stage with breath and posture:

– Sit upright with your back supported, feet on the floor, jaw unclenched.

– Take five slow nasal breaths, 4 seconds in and 6 seconds out, letting your shoulders drop.

– Soften your gaze or close your eyes if that feels better.

Step‑by‑step routine (about 15 minutes total):

– Scalp sweeps (2 minutes): With fingertips, make slow, broad circles from the hairline toward the crown and down to the base of the skull. Pressure should feel soothing, not sharp.

– Suboccipital release (3 minutes): Place the pads of your fingers just under the skull ridge. Apply gentle upward pressure, holding still for 10–15 seconds, then move laterally. Imagine lengthening the back of your neck.

– Temple and jaw (3 minutes): Lightly circle at the temples, then trace along the cheekbone. Slide to the jaw muscles in front of the ears; press gently, hold 5–8 seconds, release. Keep your teeth apart as you work.

– Neck sides (3 minutes): Using the opposite hand, glide from just below the ear down the side of the neck toward the collarbone. Avoid direct pressure on the windpipe; aim for the muscles slightly behind it.

– Shoulder roll‑outs (2–3 minutes): Pinch and release the upper trapezius (top of shoulder) with a gentle knead, then slowly roll your shoulders forward and back.

Helpful tips and guardrails:

– Use a pressure scale of 0–10, staying around 3–4 (comfortable and light).

– Avoid rapid rubbing or percussive devices during or immediately after an attack; they may aggravate sensitivity.

– A clean tennis ball in a pillowcase can provide light pressure against a wall for upper back tightness; move slowly and breathe.

– If you are pregnant, on blood thinners, have a bleeding disorder, or live with uncontrolled hypertension or significant cervical spine issues, consult a clinician first and keep touch minimal.

When to try it: many people prefer this routine during the prodrome (early warning signs) or on lower‑symptom days to support maintenance. During peak pain, just the breath work and suboccipital holds may be the only comfortable elements. Track your response for a few sessions before deciding whether it feels useful, and integrate with hydration, gentle movement, and sleep hygiene as tolerated.

Working With a Professional: What to Expect Before, During, and After

Partnering with a trained manual therapist can upgrade comfort and personalize your plan. Before the first session, expect an intake covering your diagnosis, attack patterns, known triggers, medication use (including preventive and acute), and any red flags such as sudden “worst headache,” head injury, fever with neck stiffness, new neurologic symptoms, or pregnancy‑related concerns. Share what touch has felt helpful or aggravating in the past, how long attacks typically last, and whether you experience allodynia on the scalp or face; this guides pressure and pacing.

What a migraine‑informed session might look like:

– Environment: low light, minimal fragrance, quiet space, and options for semi‑reclined positioning if lying flat worsens symptoms.

– Technique mix: gentle myofascial release for neck and shoulders, suboccipital holds, scalp work, and selective trigger point pressure if tolerated. Jaw work may be included if clenching or grinding is a factor.

– Communication: you control pressure and duration. A simple cue like “lighter” or “pause” is enough; the therapist should check in periodically.

– Duration and frequency: some people explore weekly sessions for 3–6 weeks, then reassess. Others schedule occasional tune‑ups before high‑stress periods or after a string of attacks.

Aftercare matters. Post‑session, drink water, move gently through your neck’s comfortable range, and avoid sudden heavy exertion for a few hours. A mild, short‑lived soreness can occur after hands‑on work; intense or prolonged worsening suggests the pressure was too deep or the area too sensitive, and the plan should be adjusted. Keeping a short log of sleep, stress, attack days, and session notes helps you and your therapist see patterns and refine timing, techniques, and goals.

How to choose a practitioner:

– Look for appropriate licensure or registration in your region and additional training in head, neck, and jaw work.

– Ask about experience with migraine and how they modify sessions during different phases of an attack.

– Clarify boundaries: fragrance‑free products on request, flexible positioning, and consent‑based touch for facial and intraoral jaw work (the latter only with specialized training and your explicit permission).

– If you have complex medical history, coordinate with your primary clinician so care is aligned and safe.

Finally, set realistic expectations. Massage often delivers cumulative benefits—subtle at first, then more noticeable as your system learns a pattern of softer muscles and steadier breathing. It’s most effective when it complements a broader plan that may include prescribed medications, regular meals, hydration, gentle aerobic activity, and consistent sleep routines.

Conclusion and Action Plan for People Living With Migraine

Massage can be a practical, low‑risk way to soften the muscle tension and stress that travel with migraine, especially when used consistently and tailored to your comfort. The aim is not to push through pain, but to give your nervous system calm, predictable input that reduces overall load. For some, that means fewer or milder attacks over time; for others, it provides short windows of relief that make daily life more manageable. Framed honestly, it’s one tool among many, not a singular solution.

Here is a simple action plan you can adapt:

– Track for 6–8 weeks: log attack days, intensity, sleep, and stress. Note when you use self‑massage or see a therapist.

– Practice the 15‑minute routine on low‑symptom days 3–4 times per week; during spikes, use only the gentlest elements.

– If considering professional care, schedule a trial of a few sessions and set one or two measurable goals (for example, less morning neck tightness, improved tolerance for screen time).

– Reassess monthly: if you see small, steady gains without adverse effects, continue; if not, revise timing, techniques, or frequency.

– Integrate with foundation habits: hydration, regular meals, movement you enjoy, and consistent sleep timing.

Safety recap and when to pause:

– Seek urgent evaluation for new, severe headache described as “worst ever,” thunderclap onset, fever with neck stiffness, confusion, weakness, slurred speech, visual loss, or after head trauma.

– Use extra caution if you are pregnant, on blood thinners, have a bleeding disorder, uncontrolled blood pressure, severe osteoporosis, active infection, or unstable cervical spine issues; consult your clinician before starting.

– Avoid aggressive pressure and percussive devices during or right after an attack; gentle touch is the default.

As you experiment, keep the bar realistic: you’re looking for nudges in the right direction—easier mornings, fewer jaw clench moments, and a little more bandwidth on busy days. Combine that mindset with clear communication, thoughtful pacing, and coordination with your healthcare team, and massage can take a valued place in your migraine care toolkit.